The Vineyard at Rydalmere NSW (later known as Subiaco), designed by architect John Verge for Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur and completed in 1836, is almost universally described by architectural historians as one of Sydney’s finest colonial homes.

Yet nothing of it remains on its original site and only a few architectural remnants and some items of furniture survive, dispersed in public and private collections. The Caroline Simpson Library holds some of the architectural remnants including the entrance door fanlight and sidelight; a pair of timber capitals and their sandstone bases (but not their columns); a pair of timber pilasters from the main hall; and a pair of cast iron flat grille columns.

Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur (1788-1861), a nephew of John Macarthur of Elizabeth Farm and Camden Park, purchased the Vineyard property in 1813. In 1833 he commissioned John Verge to design a large house to replace the existing Vineyard cottage, in which he lived with his wife and children. Verge was then the most accomplished and fashionable architect in the colony of New South Wales. His office ledger shows that he fixed a site for the new house close to the existing cottage which was incorporated into the offices. He supplied plans, elevations and an estimate but it seems that the actual construction was supervised by local Parramatta builder James Houison.

Hannibal Macarthur was one of numerous prosperous colonists of the 1830s who were made bankrupt in the depression of the early 1840s. He was forced to sell The Vineyard, which was purchased in late 1848 by Archbishop Polding for the Benedictine nuns as their first priory in Australia. In March 1851 the property also became a boarding school for girls and was renamed Subiaco. New school buildings were constructed in the 1850s, increasing teaching space, and a verandah was added in 1868-69 to the upper floor on front of the house to provide weather protection.

Most of the estate was sold off in the 1920s so that by mid-20th century only seven acres remained. The once pastoral area had become increasingly industrial. In 1957 the nuns sold the property to a Benedictine order of monks and three years later the monks sold the property to Rheem Australia Pty Ltd, manufacturers of hot water heaters. In 1961 Rheem demolished Subiaco to make a car park, despite a public campaign against demolition led by the NSW branch of the National Trust.

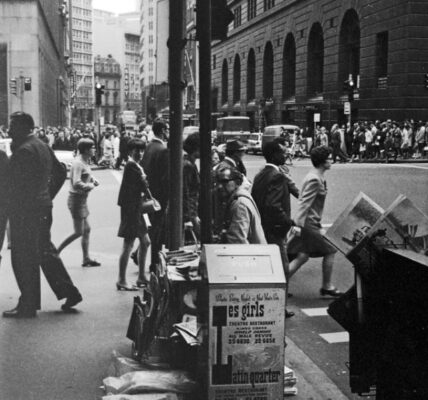

The Vineyard – Subiaco in 1961

The Vineyard was designed by John Verge in the Greek Revival style, an architectural style that had developed in Britain in the late 18th century, influenced by publications which codified a stylistic vocabulary of architectural decoration derived from new-found archaeological discoveries in Greece.

The style was fashionable in Britain in the early decades of the 19th century and that fashion was reflected in the colony of New South Wales where John Verge was one of a number of early architects who worked in the Greek Revival idiom. Surviving examples of his work include Elizabeth Bay House in Sydney, Camden Park on Sydney’s west and Aberglasslyn near Maitland in the NSW Hunter Valley.

Architectural historian James Broadbent has suggested that, in his design for The Vineyard, Verge drew on a pattern book for the front section of the house. He argues that the arrangement of the entrance hall, columned stairhall, semi-circular geometric stair and cross corridor, as well as the setting out of the colonnade were adapted from a plan for ‘a Mansion’ (Plate XV) in Peter and Michael Angelo Nicholson’s The New Practical Builder and Workman’s Companion, London, 1823. The use of a colonnade of Doric columns was a feature of Greek-revival architecture but also one that proved practical for the Australian climate.

The house at Vineyard, Conrad Martens, 1856

Conrad Martens’ 1856 watercolour of The Vineyard relates to a larger version of the picture, in oils, dated 1840 and made during Hannibal Macarthur’s ownership of the property. It shows a grand house in a bush setting, with little evidence of horticulture or landscape gardening. Yet Macarthur’s daughter, Emmeline de Falbe (1828-1911) who was born at The Vineyard and grew up there described the setting as picturesque. It was, she wrote, ‘a large property 15 miles from Sydney bounded one side by a tidal river, navigable for small steamers & on the other side extensive forests, chiefly composed of gum trees, & a good sized farm house with cultivated fields, and outbuildings ¾ of a mile from the house. Large gardens & in the heart of the forest, a semi-circular terraced vineyard, with a stream at the foot, bordered with ferns & mimosa, a lovely spot. … We lived three miles by road from the village called Parramatta, one mile through fields by crossing a river.’ (Jane de Falbe, My dear Miss Macarthur: the recollections of Emmeline Maria Macarthur (1828-1911), Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1988). Emmeline also recalled the building and furnishing of the new house: ‘Everything was done by workmen on the estate, building, furniture, & upholstery in temporary workshops at a distance. Our childish delight was to watch all these various works from the brick kiln to the carpenter’s shavings.’

Vineyard 1847

The scale and picturesque setting of The Vineyard, and the social status of the Macarthurs, meant that as soon as the house was completed in 1836, it became one of the centres of social life in the colony. Emmeline de Falbe, Hannibal Macarthur’s daughter, recalled frequent entertaining, much dancing and music: ‘We had a most pleasant circle of friends settled within easy distance, chiefly on the banks of the river. … Our Society was numerous enough to dance at home whenever we felt disposed, and our music was generally some of the regimental band placed in the colonnade outside the windows. (Jane de Falbe, My dear Miss Macarthur: the recollections of Emmeline Maria Macarthur (1828-1911), Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1988). The Macarthurs welcomed a multitude of visiting naval and military officers, Indian Civil Service officials on leave, visiting explorers and scientists. Charles Darwin went to lunch there in January 1836 with a group of naval officers from the Beagle. Ludwig Leichhardt made frequent visits and when Sir Charles Fitzroy arrived in Australia as the new Governor in 1846, he and his wife spent their initial days at The Vineyard while Government House was being prepared to receive them.

Fanlight from The Vineyard

A fanlight is an ellipitical or rectangular window placed above an entrance door in which several panes of glass of different shapes, separated by glazing bars, create a decorative effect. Fanlights became popular in Britain in the early 18th century when the best quality crown glass was available only in a limited size meaning that every window had to be sub-divided by glazing bars. By the late 18th century metal glazing bars – wrought iron or brass and later cast iron – had become common, particularly in parts of England, and in the 19th century standardised designs became available through manufacturer’s trade catalogues.

In Australia, fanlights were often one of the most decorative features in otherwise quite austere Georgian buildings of the early to mid-19th century, used in even quite humble Australian homes. Glazing bars were mostly of hand-moulded timber and rarely of the same design on any two buildings.

Entrance hall, Subiaco, 1961

In many large British homes of the early 19th century, a secondary entrance door was installed behind the main one to help exclude drafts. Fanlight designs above the secondary door were often more highly ornamented as they were protected from the extremes of the weather. The practice of a secondary door, with a second fanlight, was copied at The Vineyard with identical fanlights.

Column and pilaster, Subiaco, 1961

In some Australian colonial houses built in a Greek Revival architectural style, the style is only skin-deep. In Verge’s design at The Vineyard, the style was carried through in the internal joinery, fireplaces and especially in the entrance hall. The pair of fluted timber columns with Ionic capitals and matching pilaster (or anta) next to each one is a feature of the hall. The ‘anta’ in architecture is a slightly projecting column or pilaster produced by either a thickening of the wall or attachment of a separate strip. Although the capitals of antas/antae were not required to replicate the style of the column, the design at Vineyard clearly shows a complementary style: the anta ‘responding’ to the column.

Side elevation, Subiaco, 1961

In 1949, the Historical Buildings Committee of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (NSW branch) published a report of buildings it considered of architectural merit and worthy of preservation. Subiaco was just one of 25 buildings (and one of only nine houses) included in its ‘A’ list, the highest architectural category, comprising buildings ‘whose preservation is essential at whatever the cost.’

Subiaco was known in architectural circles but hardly part of the consciousness of the general public. In 1958, soon after the Benedictine monks had moved into Subiaco, the Sydney Morning Herald reported of the house that: ‘Few people remember it, or even guess it is there behind the barrier of factory chimneys and housetops that have encircled it.’ Subiaco did not have a strong and engaged local community to protest for its preservation when threatened with demolition in late 1960, although a strong campaign was eventually organised and the National Trust made an unsuccessful attempt to save the house through negotiation with the new owners, Rheem Australia Pty Ltd. Members of the public were allowed to see the house at ‘Open Days’ held over two weekends in June 1961 and the opportunity attracted 12,000 visitors, but one month later the house was being dismantled. Some choice architectural remnants were saved for the National Trust and the University of NSW and the rest were sold or destroyed.

Ionic timber capital, 1836

When Subiaco was demolished in 1961 a number of architectural elements were salvaged by interested parties from the architectural and preservation communities. The National Trust of Australia (NSW) acquired various elements including marble fire surrounds, which were later re-used at Macquarie Fields House in western Sydney (built c1838–40), and a stone trough that was moved to the Trust’s newly acquired Experiment Farm Cottage at Harris Park. From the University of New South Wales, Professor Frederick Towndrow (1897–1977), foundation Dean of Architecture at the University, and others in the architecture faculty, were responsible for the rescue of 16 sandstone Doric columns from the verandah of Subiaco and for their re-erection in 1966 near the entrance to the main campus. The University of NSW also acquired a number of other architectural elements, some of which were transferred to the Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection in the early 1990s.

Cast iron column, 1850s–60s

In 1961, one the eve of demolition, Subiaco comprised many buildings: the original Vineyard cottage, probably built by the first owner Phillip Schaffer in the 1790s; the 1836 John Verge designed house; a number of 19th century school buildings; and a 1908 church. This Bubb & Son cast iron flat grille column (one of two) almost certainly came from the verandah of one of the 1850s or 60s school buildings behind the main house.

The firm of Bubb & Son created castings for the engineering and building trades, operating from the Victoria Foundry in central Sydney, located in laneways between George, Sussex and Liverpool Streets. They specialised in ‘manufacturing pilasters, ornamental columns, balcony railing, wrought and cast iron palisading, and every description of iron work used in house-building.’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1868).

The foundry had been established in the 1840s but the columns are dated to the 1850s or 1860s from the foundry mark ‘Bubb & Son’. In 1852 the business had been conducted by a partnership known as ‘Bubb and Temperly’ and it was not until January 1856, when Robert Bubb was joined in partnership by his son John Robert Bubb, that the business was known as Bubb & Son. This partnership was dissolved in August 1867 following Robert’s retirement and the company traded as J.R. Bubb until 1880. A short lived ‘Bubb & Rees’ partnership followed but by 1882 the company was again trading solely under the Bubb name.

Farm buildings at Subiaco, 1961

The public campaign to save Subiaco from demolition, though unsuccessful, is now generally regarded as a key moment in the development of the heritage movement in New South Wales. The campaign created a groundswell of public support for preservation of the built environment and in the aftermath of demolition the National Trust experienced a surge in membership numbers. Later that same year Experiment Farm Cottage at Harris Park, a vulnerable early 19th century property in poor condition, became the first of many buildings purchased outright by the National Trust in order to ensure its preservation.

Activists also joined the Trust’s Historic Buildings Committee and travelled the state, identifying and listing buildings of heritage significance. In February 1962 the Trust released an ‘A’ list of 34 buildings classified as a priority for preservation. The ‘A’ list was publicized through a landmark exhibition called No time to spare which opened at the David Jones Art Gallery in May 1962, organised by the Women’s Committee for the National Trust. There was ‘no time to spare’ in the fight for these buildings, ‘the preservation of which is regarded as essential, whatever the cost.’