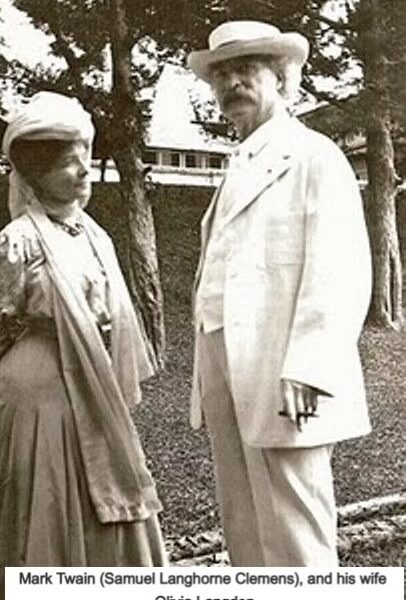

When Mark Twain—born Samuel Langhorne Clemens—married Olivia Langdon, he said something unforgettable to a friend:

“If I had known how happy married life could be, I would have married 30 years ago instead of wasting time growing teeth.”

He was 32.

Twain came from modest beginnings. He worked his way up through rough, restless trades: a printer’s apprentice, a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi, a failed silver miner in Nevada. It was only when he turned to writing that his wit found its audience and his voice made its mark on America. His words were sharp, his humor fearless, his stories unforgettable.

But none of that prepared him for love—a different kind of wildness.

He didn’t meet Olivia in person at first. He met her in a portrait. A friend showed him a locket with her face inside, and something in him stirred. The friend, sensing something more, arranged a meeting. Olivia Langdon was everything he wasn’t: refined, educated, wealthy, devout. Within two weeks of meeting her, Twain proposed.

She declined.

He was too raw. Too brash. Ten years her senior, and without a cent to his name. And though she admired his talent, he lacked the kind of spiritual conviction she had been raised to cherish.

But Twain didn’t give up.

He proposed again. And again. She turned him down again—this time for his lack of religion.

With a glint in his eye, he said: “If that’s what it takes, I will become a good Christian.”

He meant it—not as a lie to win her, but a promise to try.

Still, she said no. And he believed her.

Heartbroken but resolved, Twain packed his bags and headed for the train station. Fate, however, had other plans.

His carriage overturned on the way. And like any clever storyteller would, he milked the moment for all it was worth. Injured (perhaps more in spirit than in body), he was brought back to Olivia’s home. As she tended to him, concern in her eyes, he asked her once more to be his wife.

This time, she said yes.

Marriage softened Twain in all the right ways. He didn’t lose his fire, but he redirected it—with gentleness. He read the Bible aloud to Olivia each night. He gave thanks before meals. He stopped publishing stories she disapproved of, even if he privately found them brilliant. In fact, over the course of their marriage, he amassed over 15,000 pages of unpublished work, censored out of love for the woman he adored.

Olivia became his first editor—and his toughest.

When she read an early draft of Huckleberry Finn and came across the word “Damn,” she circled it and made him take it out.

Their daughter Susy once summed it up perfectly:

“Mama loves morality. Papa loves cats.”

And yet, it worked.

Twain adored Olivia with the kind of affection that laughs, bows, and listens.

“If she told me that wearing socks was immoral,” he once said, “I would stop wearing them immediately.”

She, in turn, called him her “gray-haired boy,” and tended to him with a mother’s care and a wife’s warmth.

One day, Twain was reading a book and laughing so hard that Olivia asked him what it was. He handed it to her, still chuckling. She looked down at the cover.

It was her book.

They suffered, like all couples do. Financial ruin. The loss of children.

But they never turned on each other.

Twain never raised his voice at Olivia. She never scolded him. When a friend made a joke at her expense, Twain—famed for his humor—nearly ended the friendship.

Love, for him, meant reverence.

At sixty, when he embarked on a grueling world tour, Olivia dropped everything to go with him. Not for glamour, but because she knew he needed care. His fire, after all, always burned brightest with her near.

Their story is not one of whirlwind romance or dramatic declarations.

It’s a story of deep compatibility, of learning and growing side by side, of laughter braided with loyalty.

Mark Twain and Olivia Langdon were opposites—morality and mischief, faith and fire—but their love lived somewhere in the middle. In the quiet evenings. In the shared pages. In the arguments avoided and the jokes shared only between them.

Their bond didn’t need embellishment.

Like Twain’s best stories, it spoke for itself.